StringTemplate is a template engine carefully designed by myself and Tom Burns (CEO jGuru.com) over many years of experience building commercial sites. Here are 3 sample sites:

StringTemplate evolved from a simple "document with holes" to a sophisticated template engine with a functional programming flavor. I chose the simple name StringTemplate to reflect my minimalist approach (its jar is about 120k with source, and class files), but to compete with other tools' names, I should have called it the He-man's Velociraptor Toolkit for Positive Text Generation Experience. <wink>

Here is the ST documentation and an academic article that might help A Functional Language For Generating Structured Text.

StringTemplate is extremely simple to use and assumes no special relationship with a web server or "engine." Further, it does not assume anything about the structure of the template text. The template can be for HTML, XML, Java, SQL, or whatever. For example, here is a trivial example that I actually use for generating SQL

import org.antlr.stringtemplate.*;

class Simple {

public static void main(String[] args) {

StringTemplate query =

new StringTemplate("SELECT $column$ FROM $table$;");

query.setAttribute("column", "subject");

query.setAttribute("table", "emails");

System.out.println("QUERY: "+query.toString());

}

}

You compile with the StringTemplate and ANTLR jars, which I have placed in /home/public/cs601 in your CLASSPATH:

/home/public/cs601/stringtemplate-3.2.jar /home/public/cs601/antlr-2.7.7.jar

javac Simple.java

and run like it like any other java program:

java Simple

The output you'll see is:

QUERY: SELECT subject FROM emails;

In my experience, the most useful characteristics of StringTemplate proved to be:

To illustrate these characteristics, consider the very real problem of having to change the way every link in your system appears. In an early version of StringTemplate, I had no way to factor out the "link" concept into a separate component. I had to change literally thousands of links by hand. With the current version of StringTemplate, I can change a single file. Changing template file link.st in my http://www.antlr.org site, for example, changes the way every link looks on the entire site. Instead of HTML HREF tags, I now use $link(url="...", title="...")$. Such easy maintenance work derives from StringTemplate's dynamic and structured nature, which supports reusing the link component.

Here is the kind of thing that I've seen in manuals for template engines that encourage rather than enforce strict separation. These all violate the rules I have outlined and represent model-view entanglements.

$if(user=="parrt" && machine=="yoda")$

$price*.90$, $bloodPressure>130$

$a=db.query("select subject from email")$

$model.pageRef(getURL())$

$ClassLoader.loadClass(somethingEvil)$

$names[ID]$

In code, you should avoid passing in any kind of output HTML:

st.setAttribute("color", "red");

While StringTemplate has evolved to support a number of advanced features, the most surprising conclusion I can draw from experience is that you need only the four features mentioned below to generate sophisticated dynamic websites while enforcing strict separation of model and view and, equally crucially, avoiding HTML and manual template creation in the controller.

The most common thing in a template beside plain text is a simple named attribute reference such as:

Your email: $email$

The template will look up the value of email and insert it into the output stream when you ask the template to print itself out. If email has no value, then it evaluates to the empty string and nothing is generated for that attribute expression.

If your controller sets an attribute more than once, then that attribute is multi-valued. Imagine the following controller code:

StringTemplate t =

new StringTemplate("Your email(s): $email; separator=\", \"$;");

t.setAttribute("email", "parrt@antlr.org");

t.setAttribute("email", "parrt@cs.usfca.edu");

where I have specified an optional separator here.

All elements are converted to text and generated in order. The output would look like:

Your email(s): parrt@antlr.org, parrt@cs.usfca.edu;

If a named attribute is an aggregate with properties (ala JavaBeans), you may reference a property using attribute.property. For example:

Your name: $person.name$ Your email: $person.email$

where you have set attribute person to be some Java object. StringTemplate ignores the actual object type stored in attribute person and simply invokes getName() and getEmail() via reflection (StringTemplate will also find fields with the same name as the property).

If an attribute reference is not resolved by looking in the associated template's attribute table, then StringTemplate searches for it in the StringTemplate enclosing template. In this way, you can set attribute fontTag once in the outermost template, perhaps page, and have all embedded templates find the value.

Instead of defining a single template per HTML page, StringTemplate encourages you to break up your pages into structured, nested templates that together combine to become a full page. This is directly analogous to how you should break down an algorithm into subprocedures. For example, if you were writing a program to generate a web page, you could make a single monolithic method:

class HomePage {

...

public void generate() {

out.println("<html>");

out.println("<head>");

out.println("<title>"+getTitle()+"</title>");

out.println("<body>");

// banner

out.println("...");

out.println("...");

...

out.println("<hr>");

// body

out.println("...");

out.println("...");

...

out.println("</body>");

out.println("</html>");

}

public String getTitle() {...}

}

But, here is a better, structured approach where the banner and body are factored out:

class HomePage {

...

public void generate() {

out.println("<html>");

out.println("<head>");

out.println("<title>"+getTitle()+"</title>");

out.println("<body>");

banner(); // replace prints with method call

out.println("<hr>");

body(); // replace prints with method call

out.println("</body>");

out.println("</html>");

}

public void banner() {...}

public void body() {...}

public String getTitle() {...}

}

The StringTemplate approach looks almost the same minus the surrounding Java infrastructure. Here is a generic page.st template file containing the overall page layout:

<html> <head> <title>$title$</title> <body> $banner()$ <hr> $body()$ </body> </html>

The template files banner.st and body.st are automatically included when a page is rendered.

All mutually-referential templates must be in the same StringTemplateGroup, which for websites loads the templates from the same directory. You will create a group object that specifies a root directory containing your templates:

StringTemplateGroup templates =

new StringTemplateGroup("mygroup", "/home/parrt/templates");

// manually ask for an ST instance

StringTemplate t = templates.getInstanceOf("page");

// t loaded from /home/parrt/templates/page.st

In this case, if the page template references another template, it will be looked up in page's group and, hence, from the same directory. You may store templates in subdirectories and reference that as $templates/misc/searchbox()$, for example.

Here is test rig:

import org.antlr.stringtemplate.*;

class ST {

public static void main(String[] args) {

StringTemplateGroup templates = new StringTemplateGroup("mygroup", ".");

StringTemplate t = templates.getInstanceOf("test"); // load test.st

... insert t.setAttribute(...) calls here

System.out.println(t.toString());

}

}

This structured approach is better as the overall page template is reusable for every page and provides a single point of change for the entire site's look. For example, to add a search box to every page, just add a reference to $searchbox()$ above the body. Further, this structuring encourages reuse of the various template subcomponents.

StringTemplate allows parameters on template includes just like method calls. An unexpected benefit of this appeared when I had to manually build a page of download items. Rather than cut-n-paste the required formatting for each download item, I used a template reference with static parameters. I still get the benefits of reuse and single-point-of-change for even manually entered information!

$download_list_item(

title="Atlassian JIRA bug tracking and project management",

companyLogo="/images/jira_logo_80_35.gif",

companySite="www.atlassian.com/software/jira/try/",

src="/download/index.jsp",

url="www.atlassian.com/software/jira/try/",

date="September 19, 2003",

description="Atlassian JIRA is a J2EE-based bug tracking ..."

)$

<br><br>

$download_list_item(

...

)

<br><br>

...

Note that I am specifying just the information and none of the formatting, which is hidden in template download_list_item.

This is the same benefit you get from using a link.st template so you can say:

Please visit $link(url="http://www.usfca.edu", title="USF's website")$ for more information.

The single most interesting and powerful feature of StringTemplate is the notion of applying a template to a list of attributes. This feature single-handedly alleviates the need for all the traditional programming constructs like loops found in other template engines.

You might ask, "How can I build a table without a loop?" Internally StringTemplate employs loops as a primitive operation, but provides the user with a much richer construct: template application.

First, let's look at how to format single-valued attributes. Imagine you have a template called bold defined in bold.st as:

<b>$it$</b>

where it is the name of the default iteration attribute. You may bold any attribute as follows:

$name:bold()$

It's like saying $bold(it=name)$, but with a different syntax. You can apply multiple templates in a row too:

$name:bold():italics()$

which yields the following if name is "Alexey":

<i><b>Alexey</b></i>

One of the key subtle points here is that your controller code is not manually creating subtemplates or inserting HTML code. Your controller merely sets attribute values.

Now to make a list of names into a bullet list, you need a template like listItem:

<li>$it$</li>

Then you can say:

<ul> $names:listItem()$ </ul>

For each element of attribute names, StringTemplate will apply the listItem template to the value. If you set attribute names to Boris and Natasha in your Java code, then the output would be:

<ul> <li>Boris</li> <li>Natasha</li> </ul>

For simple templates, you may also use "anonymous templates":

<ul>

$names:{<li>$it$</li>}$

</ul>

Or you can set your own template application iteration variable name:

<ul>

$names:{ n | <li>$n$</li>}$

</ul>

There are many situations when you want to conditionally include some text or another template. StringTemplate provides IF-statements to let you specify conditional includes. For example, in a dynamic web page you usually want a slightly different look depending on whether or not the viewer is "logged in" or not. Without a conditional include, you would need two templates: page_logged_in and page_logged_out. You can use a single page definition with if(expr) attribute actions instead:

<html> ... <body> $if(loggedin)$ $top_gutter_logged_in()$ $else$ $top_gutter_logged_out()$ $endif$ ... </body> </html>

where attribute loggedin is set by the controller. Crucially, for separation, loggedin is the result of a computation done in the model. You can only test the result in a template.

You may only test whether an attribute is present or absent, preserving separation of model and view. The only exception is that if an attribute value is a Boolean object, it will test it for true/false.

Technically speaking nested IF blocks represent an AND condition, which I'm pretty sure violates my rules, but in practice you really need this "grey area" feature.

The manner in which a template engine handles filling an HTML table with data often provides good insight into its programming and design strategy. It illustrates the interaction of the model and view via the controller. Using StringTemplate, the view may not bypass the controller and go straight to the model.

First, imagine we have objects of type User that we will pull from a simulated database:

public class User {

String name;

int age;

public User(String name, int age) {

this.name = name;

this.age = age;

}

public String getName() { return name; }

public int getAge() { return age; }

public String toString() { return name+":"+age; }

}

Our database is just a static list:

static User[] users = new User[] {

new User("Boris", 39),

new User("Natasha", 31),

new User("Jorge", 25),

new User("Vladimir", 28)

};

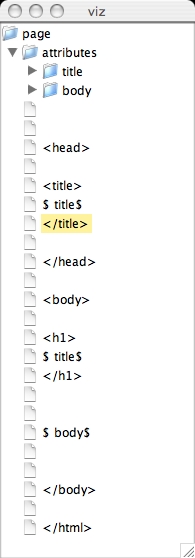

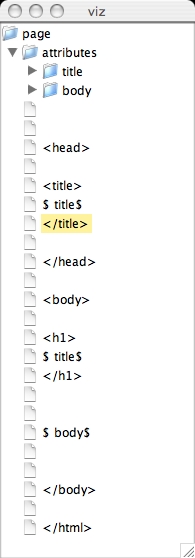

Here is my simple overall page design template, page.st:

<html> <head> <title>$title$</title> </head> <body> <h1>$title$</h1> $body$ </body> </html>

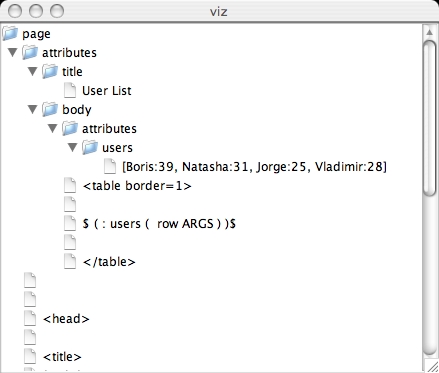

The body attribute of page.st will be set to the following template users_list.st:

<table border=1>

$users:{ u |

<tr>

<td>$u.name$</td><td>$u.age$</td>

</tr>

}$

</table>

Identifier u is the iterator parameter that will be set to each value of the users list. u.name gets the name property, if it exists, from the it object ala JavaBeans or simple field reference. That is, StringTemplate uses reflection to call the getName() method on the incoming object. By using reflection, I avoid a type dependence between model and view.

Pushing factorization further, you could make a row.st component in order to reuse the table row HTML:

<tr> <td>$it.name$</td><td>$it.age$</td> </tr>

where it is the predefined iterator when no parameter is defined.

Then the user list template reduces to the more readable:

<table border=1> $users:row()$ </table>

So now the server and templates are set up to format data. My page definition is part of the controller that pulls data from the model (the database) and pushes into the view (the template). That is all the page definition should do--interpret the data and set some attributes in the view. The view only formats data and does no interpretation.

Here is a generic page object in my server that has loads templates from the templates subdirectory (in other words, when you ask for an instance of the "page" template, it will look for it in file templates/page.st):

public abstract class Page {

/** My template library */

static StringTemplateGroup templates =

new StringTemplateGroup("mygroup", "templates");

static {

templates.setRefreshInterval(0); // don't cache templates

}

public void generate() {

StringTemplate pageST = templates.getInstanceOf("page");

StringTemplate bodyST = generateBody();

pageST.setAttribute("body", bodyST);

pageST.setAttribute("title", getTitle());

/* Uncomment to view graphically

StringTemplateTreeView viz = new StringTemplateTreeView("viz",pageST);

viz.setVisible(true);

*/

String page = pageST.toString(); // render page

System.out.println(page);

}

public abstract StringTemplate generateBody();

public abstract String getTitle();

}

A page simply subclasses and overrides getTitle() and generateBody(), which returns a StringTemplate object.

public class UserListPage extends Page {

/** This "controller" pulls from "model" and pushes to "view" */

public StringTemplate generateBody() {

StringTemplate bodyST = templates.getInstanceOf("users_list");

User[] list = users; // normally pull from database

// filter list if you want here (not in template)

bodyST.setAttribute("users", list);

return bodyST;

}

public String getTitle() { return "User List"; }

}

Notice that the controller and model have no HTML in them at all and that the template has no code with side-effects or logic that can break the model-view separation. If you wanted to only see users with age < 30, you would filter the list in generateBody() rather than alter your template. The template only displays information once the controller pulls the right data from the model.

Graphically the overall outermost template, page, looks like the following:

where the blank elements represent whitespace found in the template; they need to be separated for reasons too detailed to go into here.

Drilling down into the attributes you can see that the body attribute is set to another template with the users attribute etc...

Those graphical debugging windows are pretty handy and are conveniently generated via:

StringTemplateTreeView viz = new StringTemplateTreeView("viz",pageST);

viz.setVisible(true);

Naturally, you could go one step further and make another component for the entire table (putting it in file table.st):

<table border=1> $elements:row()$ </table>

then the body template would simply be:

$table(elements=users)$

Here is the complete source code:

and here are the templates:

The other important feature is called a StringTemplateGroup. StringTemplateGroup is a self-referential group of StringTemplate objects kind of like a grammar. It is very useful for keeping a group of templates together. For example, jGuru.com's premium and guest sites are completely separate sets of template files organized with a StringTemplateGroup. Changing "skins" is a simple matter of switching groups.

Groups know where to load templates by looking under a rootDir you can specify for the group or by simply looking for a resource file in the current class path. So, if you reference template foo() and you have a rootDir, it looks for file rootDir/foo.st.

If you want to use a different set of templates, you can simply point the StringTemplateGroup file at a different directory:

public abstract class Page {

/** My template library */

static StringTemplateGroup templates =

new StringTemplateGroup("mygroup", "anotherTemplateDir");

...

}

StringTemplateErrorListener is an interface you can implement to specify where StringTemplate reports errors. Setting the listener for a group automatically makes all associated StringTemplate objects use the same listener. For example,

static class ErrorBuffer implements StringTemplateErrorListener {

StringBuffer errorOutput = new StringBuffer(500);

public void error(String msg, Exception e) {

if ( e!=null ) {

errorOutput.append(msg+e);

}

else {

errorOutput.append(msg);

}

}

public void warning(String msg) {

errorOutput.append(msg);

}

public void debug(String msg) {

errorOutput.append(msg);

}

public String toString() {

return errorOutput.toString();

}

}

...

StringTemplateGroup group = new StringTemplateGroup("mysite");

ErrorBuffer buf = new ErrorBuffer();

group.setErrorListener(buf);

Ok, let's tie it all together: StringTemplate and servlets. Let's reuse the page.st, users_list.st, and row.st templates plus construct the dispatch servlet and some page infrastructure.

We want http://machine:8080/mail/users to yield a list of users.

Make a Page subclass called UserListPage:

public class UserListPage extends Page {

/** Our simulated database */

static User[] users = new User[] {

new User("Boris", 39),

new User("Natasha", 31),

new User("Jorge", 25),

new User("Vladimir", 28)

};

public StringTemplate body() {

StringTemplate bodyST = templates.getInstanceOf("users_list");

User[] list = users; // normally pull from database

// filter list if you want here (not in template)

bodyST.setAttribute("users", list);

return bodyST;

}

public String getTitle() { return "List of users"; }

}

The page infrastructure, class Page, creates the outer page template (site look) and requests the body. It fills in the body of the page template with the result of the body method:

public class Page {

/** My template library */

static StringTemplateGroup templates =

new StringTemplateGroup("mygroup", "templates");

static {

templates.setRefreshInterval(0); // don't cache templates

}

HttpServletRequest request;

HttpServletResponse response;

PrintWriter out;

public void generate() throws IOException {

out = response.getWriter();

StringTemplate pageST = templates.getInstanceOf("page");

StringTemplate bodyST = body();

pageST.setAttribute("body", bodyST);

pageST.setAttribute("title", getTitle());

String page = pageST.toString(); // render page

out.print(page);

}

public StringTemplate body() { return null; }

public String getTitle() { return null; }

}

We have the same Jetty servlet start up that maps URLs of the form /mail/* to our DispatchServlet:

public class DispatchServlet extends HttpServlet {

public void doGet(HttpServletRequest request,

HttpServletResponse response)

throws ServletException, IOException

{

Page p = null;

String uri = request.getRequestURI();

if ( uri.equals("/mail/users") ) {

p = new UserListPage();

p.request = request;

p.response = response;

}

if (p==null) {

System.err.println("can't find "+uri);

}

else {

p.generate();

}

}

}

Note that I've modified the constructor for Page subclasses so they does not require a constructor.

Here is the complete source code:

and here are the templates again:

Note: Make sure to save these in a templates subdirectory under where you save the Java code.

CSS is a very nice and flexible style specification for the various XML or HTML tags found in a web page. For example, I use it to alter the style of my course notes. This is what my notes looked like in March of 2004 compared to today. Literally the only difference is that I have added

<link rel=stylesheet

href="http://www.cs.usfca.edu/~parrt/lecture-wiki.css" type="text/css"

/>

to the top of the page. That URL specifies a series of rewrite rules such as:

ul, ol {

margin-top: 2px;

margin-bottom: 2px;

padding-top: 0px;

padding-bottom: 0px;

}

that specify how various tags get formatted.

Sounds great! Why do I need StringTemplate then?!

The first big reason is that you still need to generate a structured document (XML or HTML) from a servlet. You cannot use print statements, right?

Secondly, while CSS does support some content positioning, it does not support the wholesale reorganization of the data as StringTemplate does. It allows you to say how something appears relative to another element on the page or at an absolute position, but it is focused on pixels and visual-display-oriented units. StringTemplate allows you to completely reorder data. Imagine a simple template:

<html>

<body>

<h1>$title$</h1>

<ul>

$names:{n|<li>$n$</li>}

</ul>

</body>

</html>

If you wanted the title at the bottom, you can just move it in the template:

<html>

<body>

<ul>

$names:{n|<li>$n$</li>}

</ul>

<h1>$title$</h1>

</body>

</html>

In CSS, you could probably specify the proper x, y coordinates to get the title on the bottom, but it's a long process of trial and error.

You'll also find that CSS implementations are very browser-dependent even on the same operating system.

CSS is purely for display of a specific page; there is no notion of factoring out common substructures.

CSS is XML/HTML-centric and is not suitable for generating any other kind of structure text.

From a practical point of view, CSS is like the prolog language. You are listing a series of rules whose emergent behavior is a displayed page. When it's not working, you have to just fiddle with the rules and hope to find the right combination. With StringTemplate, what you see is what you get--it is the HTML page that will be displayed.

Recommendation: use CSS only to alter how individual tags are formatted.